Our second class visit was to the Tate Britain to see the work of the Pre-Raphaelites. The Pre-Raphaelites have one of the most interesting histories behind their artwork, giving their paintings a unique and recognizable style. Throughout our visit, we were able to match key facts of the Pre-Raphaelite history with techniques in the artwork.

The Pre-Raphaelites, commonly known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was a secret society of young artists that attended the Royal Academy School. Its predominant leaders were artists William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, initialed as P.R.B., wanted to overturn everything they were being taught at the Royal Academy and return to styles of early Renaissance and medieval painters. The Academy had held Renaissance artist Raphael as the pinnacle of artistic success, which the Brotherhood saw as formulaic and backward looking. The Pre-Raphaelites were inspired by the extreme details and flat compositions of the early 15th century paintings, and, most importantly, the rejection of any hierarchy of symbols in paintings, giving equal importance to all subjects and figures. The early Renaissance artists also painted on white grounds, which made their colors stand out brightly. This early Renaissance style, from which the name “Pre-Raphaelite” derived, embodied simplicity and truth in art, which the P.R.B. wanted to recapture. The artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood took a lot of heat because of their defiance against the Royal Academy rules. They were accused of using photography, a new technology at the time, to paint from. And, although they did not paint from photography, there is a sharpness to their paintings that resembles a high definition focus to photographs.

The paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites took form to show all subjects through maximum realism. No matter what the P.R.B. painted, whether it was religious, literary, poetic or alluded to modern social problems, there was always extreme detail that encouraged prolonged looking. The new process of prolonged looking gave the Pre-Raphaelites’ paintings a modern style at the time, becoming highly influential for years of artists to come. Below are some of the paintings featured at the Tate Britain, along with an analysis for each one.

Different than many of the portraits of women he painted, John Everett Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents, also known as The Carpenter’s Shop (1849-50), features six figures spread throughout the canvas. Keeping in mind the rules of the Royal Academy and the fact that the P.R.B. rejected these rules, there are aspects of this painting where one can immediately notice the defiance. First and foremost, the composition is different than the traditional paintings that were being produced at the Royal Academy. The standard composition took the form of a triangle within the canvas, with the two sides of the triangle started at the bottom left and right corners, and diagonally went towards the top of the canvas where they would meet in the middle. It was only within the triangle that the main subjects would be painted. As we can see in Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop), Millais did not follow the standard composition, and instead drew all his subjects throughout the painting, widening the focus to the whole canvas, rather than a specific area. Additionally, the colors of the painting are much more vibrant and brighter than the paintings of British art from the 1750s – 1850s. While the brown wood takes up most of the painting, Millais adds spots of color that bring visual relief to the brown. The woman kneeling in the front is wearing a deep blue dress which contrasts the bold white of her veil. Behind her, the older woman wears contrasting green and orange, also bold colors. The top lefthand side of the canvas offers a scene outdoors where we see light greens and blues, and the top righthand side shows a white corner with deep green through the window. Along with the use of bright and vibrant colors, the Pre-Raphaelies were known for their realistic representations of nature, literature, poetry, and even religion. Aside from the title of it, we can tell by looking at the painting that it is portraying Jesus Christ and his family. The red headed child in the middle holds up his hand, which has a bleeding puncture in his palm, and his feet are uncovered where we find another bleeding puncture. He is also dressed in all white, thus indicating that the child is Jesus at a young age. The woman kneeling next to him wears blue and white, a common aspect when representing Jesus’s mother the Virgin Mary. The man to the right, dressed as a carpenter, bends over to put his arm on Jesus’s shoulder, suggesting that it is probably Joseph, Jesus’s earthly father. The boy to the right of the painting, looking shameful, holds a bowl of water, also suggesting the biblical figure of John the Baptist. The other two figures seem to be a young man and an elderly woman, maybe even a grandmother. Overall, all of the figures in the painting are depicted with extreme detail. We can see the veins in Joseph’s arm, the strands of fur on John the Baptist’s skirt, the swelling of the elderly woman’s hands, and almost every piece of hair on Jesus’s head. While the detailing of the figures might make them look astonishing, the painting was rejected because of how it portrayed Christianity in an unappealing way. In the painting, the members of Jesus’s family look grotesque and, in the case of the Virgin Mary, ugly. They do not look angelic or have soft features as they usually do when they are painted. The veins in Joseph’s hand and the cuts on his knees are quite disturbing, and the swollen hands of the grandmother are quite unsettling, too. This most definitely is not a normal representation of Jesus Christ and other biblical figures, truly showing the Pre-Raphaelites’ desire to go against traditional, Academy rules.

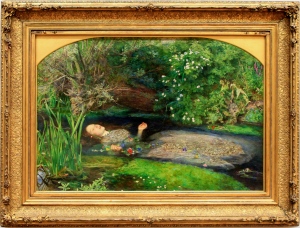

The next painting, also by Millais, is not only one of his most famous paintings, but one of the most famous paintings of all time. Ophelia (1851-2), is pictured below.

As Millais painted many, many portraits of women, this is more typical of his style than Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop) is. Ophelia embodies many of the Pre-Raphaelites’ formal techniques: vibrant colors, non-triangular composition, and minute details. Millais manages to incorporate almost every shade of green imaginable throughout the painting, along with vibrant colors in other objects. For example, the close up picture of Ophelia shows the bold colors of the flowers surrounding her in the water. Because of Millais’s minute details, we can tell what type of flowers they are, too. From the close-up picture of Ophelia, we are able to see the shading in her chin that Millais added with a soft grey color. The painting not only shows Ophelia, but an overwhelming nature scene. This is different than many of the paintings that were being produced at the time. As previously stated, the Pre-Raphaelites were interested in painting about social movements and problems, rather than traditional, Raphael-like paintings. Around the time Ophelia was painted, Darwin’s Theory of Evolution was developing and becoming increasingly known. The nature scene deputed in Ophelia alludes to the social happenings of that time, specifically Darwin’s Theory. Additionally, in the third picture, we can make out a skull within the leaves. From the full, larger view of the painting, it is hard to notice the skull. However, like a typical Pre-Raphaelite painting, prolonged looking is necessary to see all the details in the work.

While we looked at many beautiful paintings, the last one worth noting is The Awakening Conscience (1853) by William Holman Hunt. The painting is pictured below.

The Awakening Conscience was one of the more criticized paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, not only for its formal aspects, but for its suggestions about society at the time. For a formal analysis, we see again the common techniques of P.R.B. paintings. There are a vast amount of bold, bring colors throughout the painting and the detail within the painting is astonishing. From the lace of the woman’s dress, to the pattern in the blanket, to the reflection of the garden outside, Hunt manages to add in every detail he possibly could. So much detail, in fact, that it looks like a photograph in some ways. For example, the second picture shows Hunt’s ability to play with color to create light. By focusing in on this corner of the canvas, it looks more like a photograph than a painting. This is a prime example of why critics of the Pre-Raphaelites thought they used photography to draw from; their detailing and manipulation of color was so intense that it looked real. As for perspective, Hunt gives more depth to the painting by adding in the reflection of the garden outside a window in the back. Without that window and the reflection, the painting would seem much more shallow. While the formal aspects of the painting are fascinating, the underlying message of The Awakening Conscience is a societal commentary. As pictured, there is a woman sitting on a man’s lap. However, they do not seem like they are husband and wife. Rather, it is a middle-class man and his mistress that are painted. From the space of the room, we can tell that it is not the house of an upper-class person. Additionally, we can tell from the various items lying around the room and its “messiness” that the relationship is a bit more whimsical, again implying that the woman is a mistress. Her gaze into the distance fits the title, as she does seem to be “awakened,” perhaps by something that the man is saying or doing. While she may be his first choice at the time, she is a mistress, after all. Mistresses are known to be discarded after a period of time, and there are a few details within the picture which imply her eventual “discard.” First, there is a single glove lying on the floor by the mistresses’s feet (more visible in the second picture). The glove, which seems to have been thrown without a care, can imply that the mistress will eventually be tossed, too. Additionally, the cat and bird below the table on the left of the painting (more visible in the third picture) show the cat trying to reach and hold down the bird. The cat grabbing the bird can signify what is going on between the man and woman above them; the man, with more power than the mistress, can determine when she will be discarded. Until then, she is his, and he calls the shots. With all that this painting implies, it was really a commentary on society at the time when it was painted. Again, something the Pre-Raphaelites were known for doing.

I’ve always known that knowing the history behind an artist and the time of the painting helped understand it. However, nothing drove home that fact better than visiting the Tate Britain and seeing the Pre-Raphaelite paintings. The Pre-Raphaelites have, by far, one of the most interesting histories behind their artwork. Not only are their formal techniques so radical, but the context and reasoning behind their paintings are, too.

This is amazing and very interesting. Thank you for breaking it down and helping me appreciate these paintings.

LikeLike