For our third week of class, we returned to the National Gallery to look at work from the Impressionism and Post-Impressionism movements. A handful of the paintings from these art movements are some of the most popular paintings of all time, including works from popular artists like Manet, Monet, Van Gogh and many others. The trip started off by looking at works of Impressionism. The 1860’s marked another time where artists were radically changing the art game. Edouard Manet’s exhibition left visitors shocked as he featured paintings of modern life. He was one of the first artists to do so. Capturing aspects of contemporary life lead to new painting techniques, such as rapid, sketch-like brushstrokes and bright colors. These techniques were continuously practiced by other artists who were inspired by Manet, such as Claude Monet and other young artists in Paris at the time. Within the beautiful city of Paris, these artists often painted along the river Seine. Working to incorporate fleeting effects of light and color in the water, flickering brushstrokes were popular among these artists to successfully paint what they were experiencing. As we saw with the Pre-Raphaelites, this radically new way of painting was not fully accepted by society at the time, so the artists banded together informally to advance their art and help organize an exhibition of their works in 1874. From this exhibition, the artists and their works were dismissed as merely “impressionist.” Because of the informality of the group, artists went off in their own directions and became less cohesive. However, Monet remained loyal to the Impressionists style, which is why many of his works are still popular today. His continuous exploration of light and color in different conditions and times of day show the range of what he was able to paint.

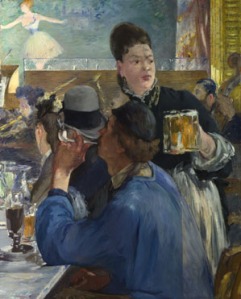

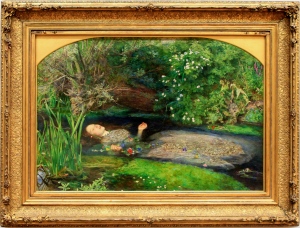

While there were many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists to see at the National Gallery, this blog post will cover just a handful of the most important and influential artists of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. We will start out with Edouard Manet. Manet was known for his unconventional subject matter. He paintings were of modern life, and his concern for the artist’s freedom in handling paint made him an important precursor of Impressionism. His work was established on the opposition of light and shadow, a restricted palette where black was vital, and on painting directly from the model. Manet was highly influenced by Spanish painter Velázquez, whose style he adopted. We can see similarities between the works of Velázquez and Manet below in two of their paintings. The first is Corner of a Café-Concert (1878-80) by Manet, and the second is Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1618) by Velázquez.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/manet-corner-cafe-concert-NG3858-fm.jpg)

There are many techniques in this painting that are specific to Manet and his Impressionistic style. First off, the subject matter of the painting is something completely different than what had been painted up until this time. Manet is depicting a scene of modern life, which was something not typically painted by artists. Additionally, the brushstrokes of Manet’s painting are different than what was typical of the time. His brushstrokes were rapid and sketch-like. We can see throughout the canvas the different and defined brushstrokes. This technique was one that would influence painters after Manet, such as Monet and other young artists in Paris at the time. Manet was known for his painting of light, shadow and limited color choice. Towards the top left of the canvas, Manet chooses lighter colors to show that the ballerina, and the stage she is on, are lit up by spotlights. As for the rest of the canvas, there is a darker tone with similar colors, such as blacks, greys and blues. There are some yellows, browns and whites, however they are in no way overpowering. There are no bright, bold colors in this painting by Manet, but we do see his love for the color black as it makes up many objects in the painting, such as the waitress’s blouse, the man’s hat, the bassist’s hair, etc. The back color is even used to show shadows throughout the painting – another technique specific to Manet as he was known to paint the difference between light and shadow.

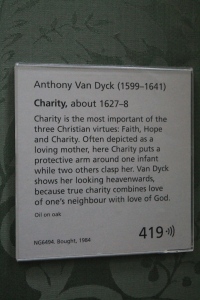

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/velazquez-christ-house-martha-mary-NG1375-fm.jpg)

In this painting by Velázquez, we can see the similarities between his and Manet’s work. As for the subject matter, it does allude to Christ and a biblical scence. However, it is not a typical biblical scene as it is seems to be depicting a honest, contemporary view of the main woman in the painting working. As for colors, we can see that Velázquez also had a limited palette. There are mainly browns, reds and greys in this painting, with some touches of blue and white. Additionally, Velázquez plays with shadow and light between the foreground and the background in the top right of the canvas. The foreground seems to be in a darker room, whereas the background in the top right corner seems to be a bright room separated by a window. Velázquez’s creation of the small window plays with space and creates a deeper perspective within the painting. We could point out a similar point in Manet’s painting as he played with light and shadow to show the ballerina in the far background of the painting and gave us (the audience) the perspective that we were in the foreground with the waitress. Between all of these similarities, it is obvious that Manet was highly influence by Velázquez.

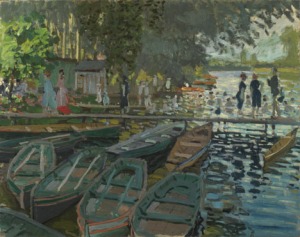

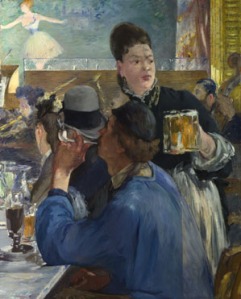

Just as Manet had a huge artistic influence, he was himself a huge artistic influence to many artists in Paris, especially Claude Monet. Manet influenced Monet’s figure compositions during the 1860’s. The Impressionist period cannot be discussed without mentioning Monet. His techniques and talent are the reason he is so popular and his paintings are so widely known around the world. Monet was, by far, the leading French Impressionist landscape painter. Born and raised in Paris, many of Monet’s paintings focus on a single subject in different lighting conditions throughout the Parisian land. In Paris, Monet met other painters such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. The National Gallery has a huge collection of Monet’s work. Room 43 consists of Monet’s earlier paintings. Two of them are featured below.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/monet-bathers-la-grenouillere-NG6456-fm.jpg)

The above painting, Bathers at La Grenouillère (1869), shows a popular boating and bathing sight on the Seine near Monet’s house in west Paris. The most obvious technique of Monet is his brushstrokes. Just like Manet, he used shorter, more defined and sketch-like brushstrokes. However, Monet’s seem even more defined than Manet’s do. Although Monet uses a wider color palette, we do see the Manet’s influence on the difference between light and shadow in this painting. In the foreground, Monet uses darker colors to paint the boats and show that they are covered and completely in the shade due to the trees that seem to be arching over the boats. As for the background, that is were Monet uses lighter colors to show the source of the sun’s light. The lighter colors in the background show the sun reflecting in the water of the Seine and the bathers in the river. We can also see another light source to the very left of the painting, where there appears to be an opening in the trees and the sun shines through. What is most impressive about Monet’s techniques in this painting is the way he shows the ripples in the water. Switching between light blues and other colors (such as the dark to reflect the women in black, or the green to reflect the tree’s leaves), we get the sense of waves and ripples in the Seine, perhaps from the movement of the bathers swimming around in the water. Overall, Monet’s brushstrokes add a texture and detail to all the subjects within the painting. Every tree, person, boat, etc. can be made out thanks to Monet’s way of painting.

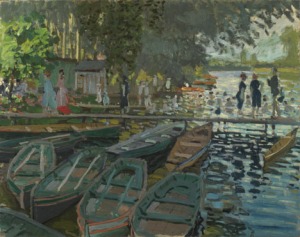

Another work that shows Monet’s famous Impressionist style is his painting The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil (1872), pictured below.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/monet-petit-bras-seine-argenteuil-NG6395-fm.jpg)

As previously mentioned, Monet focused his paintings on depicting a single subject in differently lighting conditions. This painting again shows the River Seine that Monet painted so often. However, as influenced by Manet, Monet plays with light differently in this painting than he did in the previous. In this specific painting, there seems to be little shadow featured, however it appears that the scene as a whole takes place outside while it is overcast and cloudy. Monet’s color palette contains mostly earth tones that are fairly the same. The lighter colors are again featured in the Seine where Monet shows his talent by painting the movement in the water and the shadows of the trees along the river. Although there are not as many short, sketch-like brushstrokes in this painting than the previous, we can still see some of those Impressionist-like brushstrokes in the grass in the foreground and the River Seine.

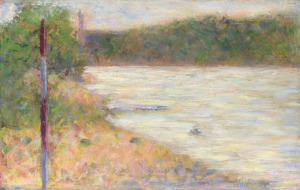

After looking at many paintings from the Impressionism movement, we moved onto Post-Impressionism. One of the leading Post-Impressionist painters was George Seurat. His specific style was different than that of the Impressionists. Seurat strayed away from the apparent spontaneity and rapidity of Impressionism and developed a structured, more monumental art to depict modern life. At the beginning of his painting career, he followed a more traditional path, being taught to paint at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, studying the works of early Italian and 17th-century French artists in the Louvre, and exhibiting his works at the official Salon. Seurat not only combined his traditional approach to art with the study of modern techniques, but he also applied ideas from contemporary optical theories of color relationships. His disciplined work, although it contrasts with many of his Impressionist contemporaries, was extremely influential. Below are two of Seurat’s paintings.

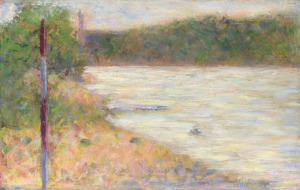

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/seurat-river-bank-seine-asnieres-NG6559-fm.jpg)

The above painting by Seurat is A River Bank (The Seine at Asniéres) (1883). Because Seurat followed traditional teachings of art, the subject matter is not as radical in this painting as the subject matter had been in previous artists. There is no depiction of modern life, which is odd in Seurat’s case as he as inspired by modern life. However, it make sense, being taught the traditional rules of art, that he would depicting a landscape rather than modern Parisian life. Because he did have a more structured approach to his art, there are aspects of the painting that are very organized. For example, the composition of the painting is very geometric due to the guiding lines. There is a vertical pole to the left, which is again mimicked in the background of the painting more towards the center. There are horizontal lines with the back shoreline of the river, which are again repeated with the horizontal line of the horizon in the background. Additionally, the diagonal line of the riverbank in the foreground seems to lead out of the bottom right corner of the painting, rather than a random spot along the border of the painting. This painting is a great example of Seurat’s deliberately structured approach to his works.

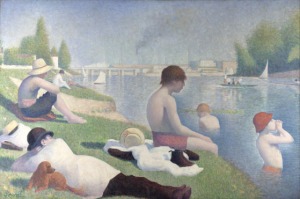

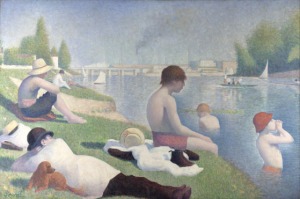

The second painting by Seurat, Bathers at Asnières (1884), is pictured below.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/seurat-bathers-asnieres-NG3908-fm.jpg)

This painting by Seurat is one of his most famous. It is the style of this painting and the techniques used that truly embody Seurat’s way of painting. In this specific work, we see that modern life was the subject matter, as many of Seurat’s paintings were. Although his style of painting did not mimic that of the Impressionists, Seurat still was influence to depict modern life and contemporary Paris. Composition-wise, the figures are clean cut and spread throughout the canvas. We see horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines throughout the canvas, as well. The horizontal lines appear in the background with the bridge. The diagonal lines are seen with the direction of the river, the slant of the hill, and even the direction of the man’s body laying in the foreground with the small dog. As for vertical lines, the figures standing, sitting straight up and the trees in the background on either side of the canvas allow the eyes to see the vertical movement throughout the painting. Together, all three directions create movement and allow the eye visual relief since there are no overpowering lines of one specific direction. As for colors, Seurat sticks to a lighter palette for the most part. However, the dark reds and oranges seen in the man’s pants, the shoes of the person sitting on the edge of the bank side and the figures’ hair are bold statements against the light greens and blues. As we can see, Seurat uses light colors very faintly around the figures in the water, almost giving them a halo effect, to stand out against the blue. He also adds some dark blue around the figure in the center, for example, to further emphasize the figure’s outline. One of the most important things to mention about Seurat is his invention of pointillism. It was a technique he used in which he would create countless tiny dots of pure color placed in extremely close proximity to each other. When viewing these dots at a distance, the human eye is meant to fuse the individual dots together so that they turn into areas of solid color to the viewer. Even though Seurat initially did not use pointillism in this painting, he returned to it after it was finished and added dots of contracting colors to created vibrancy and luminosity. One of the areas he added these dots are in the boys hat, where there are now orange and blue dots.

One of the last artists we looked at was Cézanne. Although he was associated with the Impressionists, he had another agenda art-wise. He claimed that his ambition was to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable like the art of museums.” His work, discovered by the Paris avant-garde during the 1890’s, had significant influence on Picasso and the development of 20th century art. Born in Provence, Cézanne frequently visited his birthplace throughout his life, as he was obsessed with its dramatic landscapes. He had many, many influences, including Courbet and Manet earlier in his career. His earlier works often mimicked Courbet, as Cézanne would apply thick layers of paint with a palette knife. In the 1880’s, his brushwork became more and more systematic and ordered. Starting to place more emphasis on structure and solidity by using color instead of light to convey forms, Cézanne worked slowly and methodically. He carefully selected subjects he could study for long periods of times. Later in his career, his innovative compositions won over the respect of younger artists like Picasso, and fundamentally affected the course of 20th-century art moving forward. Two of his paintings are shown below.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/cezanne-landscape-poplars-NG6457-fm.jpg)

As one of his earlier paintings, Cézanne’s Landscape with Poplars (1885-7), shows many of the techniques that were specific to his painting style. Knowing that Cézanne was obsessed with Provence, it is safe to assume that the landscape depicted is of his birthplace in France. As his brushwork became increasingly systematic and ordered in the 1880’s, we can tell that this painting was from that time period without having to look at the year it was created. We can especially see the methodical brushstrokes in the grass painted in the foreground. Even the trees and house they surround are painted with careful brushstrokes, as they are all defined and separate, not sketch-like or blending into each other as they might have for another Impressionist painter. When looking at the painting, we can see different shades of green within the grass, and we are able to tell where the sun hypothetically should be hitting the grass and the house and the tress. To convey the light source and the shapes of objects, we see Cézanne’s method of using different colors rather than playing with light or white paint. Cézanne uses colors to show different patches of grass, the outline of the house, the perspective of the trees, etc. In his next painting, Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses) (1894-1905), we see many of the same techniques.

(source: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/upload/img/cezanne-bathers-les-grandes-baigneuses-NG6359-fm.jpg)

Although this painting of Cézanne’s was later in his career, we still see many of the techniques that are specific to his work. First off, Cézanne again plays with color to show forms rather than playing with light. He has outlined all the figures with shades of blue to not only separate them, but show their shadows, as well. The coloring of his figures also varies, with lighter bodies in the back and more yellow bodies in the front. This could be to show where the light source was coming from in the painting. Overall, his variation of color throughout the canvas allow him to define the different objects and the depth of the painting instead of using white paint or light to do so. Cézanne’s brushstrokes are not identical to the ones of the previous painting, however they still appear to be orderly and structured. In the above painting, the brushstrokes seemed to be continuous short lines, whether they were going horizontally, vertically or diagonally. Here, in this painting, the brushstrokes seem to be more blended and free, and less “line” like. This creates a bit more movement throughout the painting and softens it up, too. While the subject matter is not Provence, we still see an element of nature to the painting, mainly indicted by the colors and the background of the canvas. Cézanne’s ealier work, like the previous painting, had simple compositions. However, in his later works like the painting above, he developed more complicated compositions. We can see in Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses) that Cézanne has mainly diagonally lines as opposed to horizontal or straight lines. The diagonal lines go in all directions, however they all seem to lead towards the middle of the canvas as if it is the main focus. This is an example of how innovated Cézanne was with his compositions. Comparing his two paintings above, we can see the development of the artist’s abilities throughout his career.

While we saw many artists at the National Gallery, the ones above were worth mentioning. Their talent not only influenced artists in the following years, but it is the reason that these paintings are still so famous today. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists radically changed the art world and produced works that captured expertise and skill.